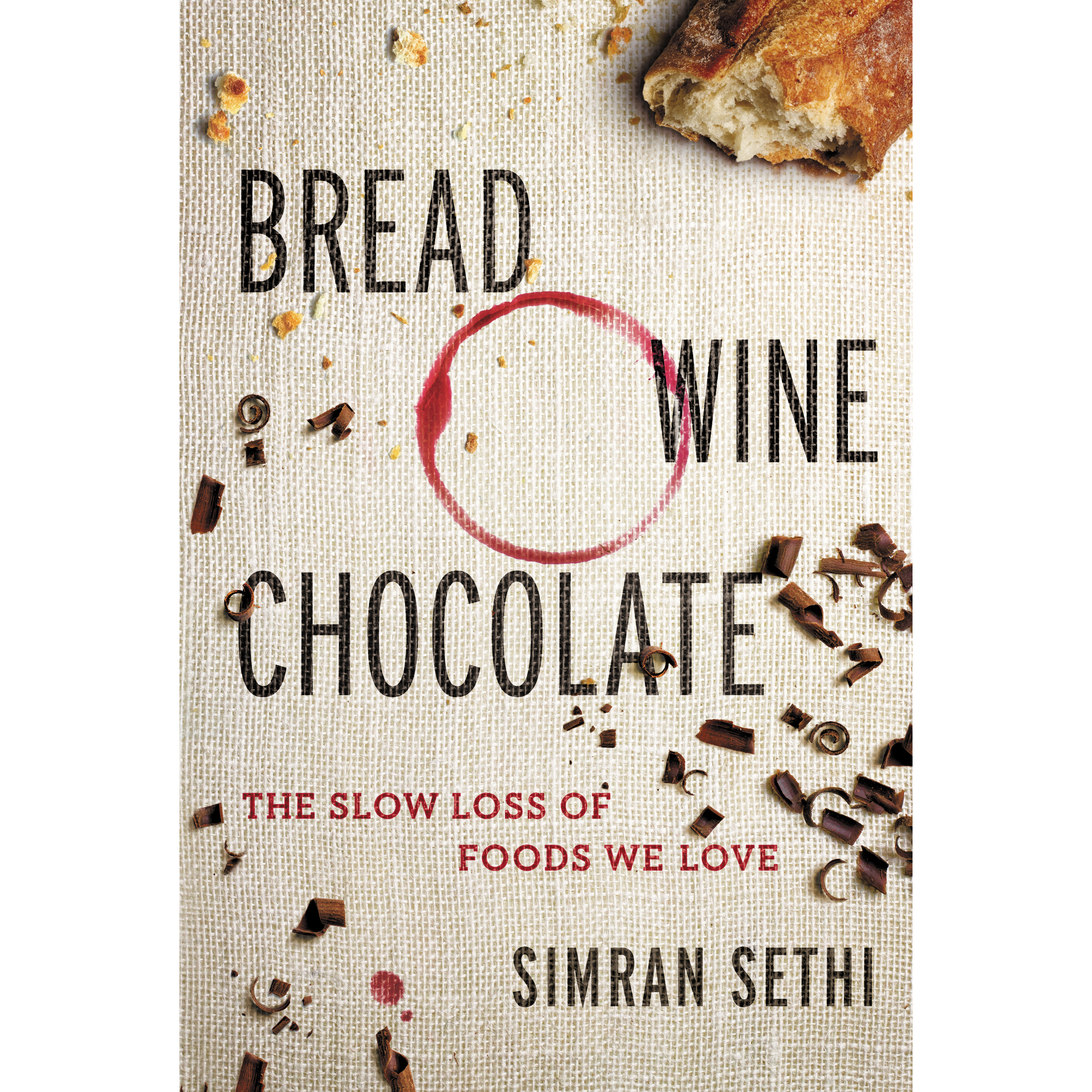

The Slow Melt Is the Chocolate Podcast You Need to Hear

“The story doesn’t start at the chocolate factory. It starts long before that,” says Simran Sethi, author of Bread, Wine, Chocolate: The Slow Loss of Foods We Love and creative force behind The Slow Melt, recently named “Best Food Podcast” by the editors at Saveur.

Launched in January 2017, The Slow Melt acts as a platform for the “deep exploration” of chocolate, highlighting the varied stories of the individuals, trends, practices, technology, and cultural mores that influence its production.

“There’s maybe this idea in media that chocolate is something you talk about through recipes or food trends,” Sethi explains of the origins of The Slow Melt. “But for me, these are stories about science, about climate change, about flavor. There’s so much that can be explored through this one substance. I remember pitching a story last June and the editor got back to me in five minutes and said, ‘This isn’t chocolate season.’ I thought to myself, ‘Woah! I eat chocolate every day, I don’t know what you’re talking about. It’s grown right now.’

Following this interaction, Sethi was inspired to create her own narrative space. “There were so many stories that I wanted to tell,” Sethi continues, referencing time spent researching for her book in major cacao-producing countries like Columbia, Ecuador, Papua New Guinea.

“I decided I would just start my own podcast, so I would be able to share some of these stories, and shift the focus back to farmers. I think the dominant narrative around farmers is: ‘Poor people grow this food,’ and that’s it. We don’t really hear from them, we don’t know where they come from… Those stories are important, and to shine the spotlight on makers is a great thing, but I don’t want it to be to the exclusion of all the other people who enable chocolate to exist.”

Each episode of The Slow Melt focuses on a different part of the production chain, addressing everything from economic ramifications (“The High Price of Cheap Chocolate“) to how sound factors into enjoyment (“Eat with Your Ears“). Running parallel to these thematic episodes is the Maker Series, a collection of profiles highlighting some of the more interesting producers in the world of chocolate, like Fruition, whose Corazon de Dahlia bar (milk chocolate, passion fruit, quinoa, lime, salt) is one of Sethi’s all time favorites (and yes, she eats chocolate on the regular– for the sake of her job, of course).

For those who want to eat along with The Slow Melt, all of the bars featured are sold in bundles by Chocopolis (in the US) and Bean Bar You (in Australia).

In drawing out these details and metaphoric flavors, Sethi sees The Slow Melt as helping to create and cultivate a culture of chocolate, much like what has historically existed for wine, and which has developed in recent years around beer and coffee. But for chocolate in particular, the politics of its increasing popularity are wrapped up in the inequalities of global economies.

“Sethi sees The Slow Melt as helping to create and cultivate a culture of chocolate, much like what has historically existed for wine, and which has developed in recent years around beer and coffee.”

“If you look at something like wine, the places where the grapes are grown is typically where the wine is produced, like Napa or Provence,” Sethi points out. “But when it comes to coffee and chocolate, they’re really de-coupled. The crops are grown in one place– the Global South, typically significantly poorer countries– and are turned into the high value good in the Global North– so Europe, or the United States, or Canada. If farmers and cocoa producers could keep that money in the local economy that would really transform the situation not only for the farmers, but also for those involved throughout the supply the chain.”

Yet despite the growing popularity of artisan chocolates, the economic forecast remains dismal; this year marked the second in an oversupply of cacao, which has had dire repercussions.

“You have farmers who are already very poor (for example in Ivory Coast, they’re making 91 cents per day) now losing 50% of the value of the crop they put in the ground,” Sethi reveals.

“This is a tree that takes five years to mature. We’re not talking about someone who can quickly course correct and start growing something else… Keeping some of that money in that domestic economy would give [farmers] more power when it comes to this price volatility. Or if not power, at least stability.”

Ecuadorean farmer Vicente Norero assessing harvested cacao pods.

In providing this information to listeners via an easily digested podcast, Sethi is helping to inform consumers, which in turn supports the sustainability the craft chocolate movement (in creating a demand for different cacao cultivars) by nature preserves.

“The craft chocolate movement– like craft beer, like the speciality coffee movement– offers the opportunity to celebrate flavor, to celebrate the artisanship that goes into making these products,” Sethi argues. “It is the area that holds the greatest hope, because it’s the only realm in chocolate that celebrates biodiversity. When you get a Snickers bar, you want it to taste the same all the time. To create that experience of familiarity requires pretty extraordinary manipulation. But when you’re eating that, you’re eating the nuts, the caramel, the chocolate. In the United States, you’re only required to have a 10% cocoa content to call a bar a ‘chocolate bar’. The more appropriate designation would be candy bar. You see the bars that are 60% cocoa, 70% cocoa– those are the bars where the cocoa is really going to shine through.

“Not only does the flavor matter, we are going to celebrate the terroir of chocolate,” Sethi says. “We know that a Chardonnay from Napa is going to taste very different from a Chardonnay from France. We expect that, we celebrate it… That cocoa-y flavor is the baseline flavor that we see from cocoa beans is from Ghana. I like to think of the cocoa from Trinidad as having this really deep fermented flavor– it reminds me a lot of raisins and dried figs. You can’t find that in 10% bars with nougat and peanut. That’s what ‘craft’ holds. It holds the possibility of celebrating flavors. Because the price point is higher, it reminds people who we’re not paying enough for this product. What do you get for a 99 cent bar of chocolate versus a $10 bar of chocolate? Why is the price differential so great? That education is happening in real-time.”

Cross-section of fresh cacao seed.

For the average chocolate shopper, The Slow Melt creates a means of understanding what exactly it is they are buying, and why it might have a steeper price tag.

“If you’re going to drop $10 on a bar of chocolate, it should be delicious!” Sethi adds. “It should be interesting, it should be something that supports the kind of agricultural system you want to see flourish. There’s a lot of confusion over what is fair trade. What is the difference between a cocoa bar that has 50% cocoa content and 70%? It doesn’t mean one will be more delicious than the other, it’s simply a percentage. People have gotten really confused about what good chocolate is and what good chocolate can be.”

In particular, Sethi is wary of the recently popular “bean-to-bar” designation.

“The biggest manufacturers in the world have greater control from bean-to-bar than most small makers,” Sethi reflects. “The idea of working from the bean somehow makes the chocolate more virtuous is misguided. I think ‘bean to bar’ is going to go the way of GMO confusion. We breed crops. We cross crops to breed them. That‘s genetic modification. Now what the GMO designation is meant to imply is the recombinant DNA technology, which is a different kind of breeding. But consumers are really confused. When companies or scientists come out and say, ‘All foods are genetically modified,’ what is a consumer to do? I think ‘bean-to-bar’ is going to go the same way. It’s going to mean everything and nothing. It’s a terrible way to delineate what craft chocolate or speciality chocolate is.”

Looking ahead, Sethi sees several trends emerging in the world of chocolate, in particular around redeeming otherwise ‘lesser’ forms of chocolate, like milk-chocolate and white chocolate.

Chopped chocolate.

“[White chocolate] used to become this hyper-sweet confection and a lot of people say it’s not even really chocolate because it has no cocoa nibs in it, it just has cocoa butter,” Sethi reflects. “What we see now is white chocolate now has a much lower sugar content and has really interesting inclusions. There’s a white chocolate maker in upstate New York named Bryan Graham, and he has a white chocolate bar that has corn in it. There are these wonderful inclusions with mango that are made by SOMA chocolatier in Canada… There’s this focus on using the cocoa fat or cocoa butter (the terms can be used interchangeably) as the platform for the exploration of flavors. Using savory inclusions like salted almonds, nettles, broccoli powder– all kinds of things are being introduced into these bars.”

Beyond its far-reaching topics and aspirations, The Slow Melt has a personal dimensions as well; in many ways, The Slow Melt is a reflection of Sethi’s own journey and relationship with chocolate.

“I’ve had a lifelong love of chocolate, but I never viewed it as anything but a treat. As I write in the book, chocolate was my every birthday cake, my wedding cake, it helped get me through my divorce. It has been my steady culinary companion,” Sethi says.

In charting her own understanding of chocolate, Sethi hopes others will be inspired to embrace chocolate’s biodiversity– an important part of ensuring cacao for future generations.

“When it comes to biodiversity in our foods, we need this biodiversity because we increasingly grow a very narrow spectrum of crops and raise a narrow spectrum of livestock for our sustenance. We choose the ones that are shelf stable, that have higher yields,” Sethi tells us. “We don’t often save crops for flavor and even nutritional value is quite secondary.”

By developing the world and stories surrounding chocolate, The Slow Melt— much like the slow food movement– stresses that food isn’t just about survival. It’s about enjoying what makes life worth living, too.

To learn more about The Slow Melt, visit their website.

Hungry for more? Check out our profile of Heritage Radio Network, a Brooklyn-based radio station that serves up daily stories about what’s new in the world of food.