How Richard Brautigan’s Please Plant This Book Kickstarted a Revolution

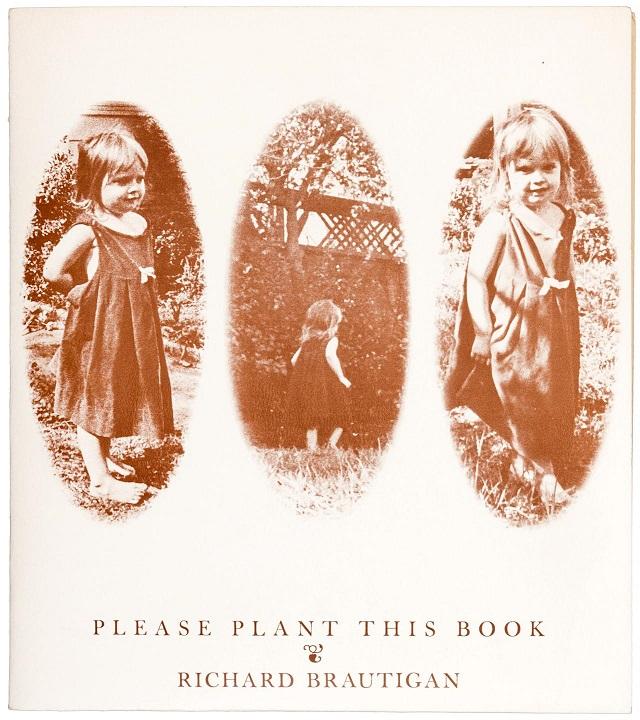

When Richard Brautigan published Please Plant This Book, a collection of eight poems printed on seed packets housed within a folder, he was ensuring that both art and food were accessible to all.

On the first day of spring in 1968 when his book was first published, it was free, as Brautigan had granted permission for anyone to reprint the book with one condition: that it couldn’t be sold.

True to its eponymous credo, Please Plant This Book was unconventional, imaginative, and caused a bit of an uproar among a group he was said to be apart of called The Diggers, an anarchist guerrilla street theatre group that challenged the emerging counterculture of the ‘60s.

The Diggers wanted a society free of private property, and while Brautigan was making seeds– and therefore food– more accessible, he was also self publishing, writing for Rolling Stone, and recording spoken-word albums for The Beatles. Digger or not, he created a new way for people to consume content and with that, a new way for them to think about the cultural importance of food.

While Brautigan was making seeds more accessible, he was also self publishing, writing for Rolling Stone, and recording spoken-word albums for The Beatles.

Some say the inspiration from this book, which contained four flower and four vegetable packets with poetic prose dedicated to whichever vegetable or flower the seeds could yield, was a rock concert called the Festival of Growing Things, which took place in July 1967. (All that attended the weekend festival at Mount Tamalpais Outdoor Theater received seeds.)

As Brautigan wrote in his poem Shasta Daisy: “I pray that in thirty-two years passing that flowers and vegetables will water the Twenty-First Century with their voices telling that they were once a book turned by loving hands into life.”

Today, nearly 50 years later, we are just beginning to understand the significance behind what Brautigan was saying. These flowers and vegetables that surround us should have a history, a diversity, and an ex situ preservation strategy– a practice of protecting seeds in gene-banks so that their story can live on for many years.

Without these efforts, packets of seeds won’t be accessible for purchase at your local nursery; they won’t arrive complimentary with your check at The LINE Hotel; and they won’t be given freely on the first day of spring in Golden Gate Park, a tradition that Brautigan once facilitated.

We are living in an age where every seed patent, from corn to cannabis, can be owned. This began with innovation in the horticultural industry, as plant breeders perfected the amount of petals that a ranunculus could yeild or controlled how perfumed a rose could smell, and this has become interminable in modern day agriculture.

For us to regain agency, we must rewrite our current narrative of how plants are grown, connect with the land by growing plants ourselves, and help seed banks preserve heirloom varieties. Brautigan knew the significance of seed preservation then, and his work continues to inspire the next generation to reinterpret the significance of it now.

Just two years ago, Please Plant This Book inspired Argetine publisher Pequeño Editor to launch a campaign that turned popular children’s books into books made from recycled paper printed with biodegradable ink and hand-sewn bindings. In the first of the Tree Book Tree series, [easyazon_link identifier=”9871374062″ locale=”US” tag=”gardcoll03-20″]Mi Papá Estuvo en la Selva[/easyazon_link] (My Dad Was In The Jungle) by Gusti Llimpi and Anne Decis, Jacaranda tree seeds are embedded the paper, which is capable of growing a tree when planted.

On March 20th, 2018, Francis Daulerio will also release a 50th anniversary reinterpretation of Brautigan’s Please Plant This Book to benefit The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Nature, in this way, has always been a literal and metaphorical place of refuge and solace.

Still, Americans don’t require an anti-establishment movement to change seed culture: making seeds accessible to all is enough. Many of these changes are already being made, but the movement is in constant need of public awareness and support.

Farmers are lobbying against seed patents from large corporations like Monsanto at the time of this writing, seed saver exchanges are popping up everywhere, and organizations like the Center for Food Safety are increasingly spreading the word about the importance of heirloom seeds (and encouraging strict pesticide regulations, as unregulated chemicals sprayed on food often have the additional adverse effect of harming bees).

To help farmers in Puerto Rico rebuild their agriculture after the devastating effects of Hurricane Maria, for example, people can donate seeds to Delaware Valley University, who are working with an agronomist and seed researcher to help restore land that was damaged in the storm.

Buying heirloom varieties of common vegetables like tomatoes and potatoes also goes a long way to improve food security (heirloom produce has the added benefit of being more nutritious than conventionally-grown varieties, as well).

And for DIY growers in the spirit of Brautigan, the Hudson Valley Seed Company is also making heirloom and open-pollinated garden seeds more accessible than ever– because change, as always, is often initiated in one’s own backyard.

Want to learn more about seed saving? Read our article on the global importance of seed banks.