The Idyllic Hollywood Story Behind The Moorten Botanical Garden

Nestled on a discrete stretch of South Palm Canyon Drive in a neighborhood defined by charming mid-century modern homes, the Moorten Botanical Garden in Palm Springs is one of the most alluring desert gardens in the world. Visitors to this unique botanical refuge are apt to feel like they’ve encountered something out of a fairytale, as the incredible, privately-owned oasis seems to hide from view, behind sturdy, unassuming gates.

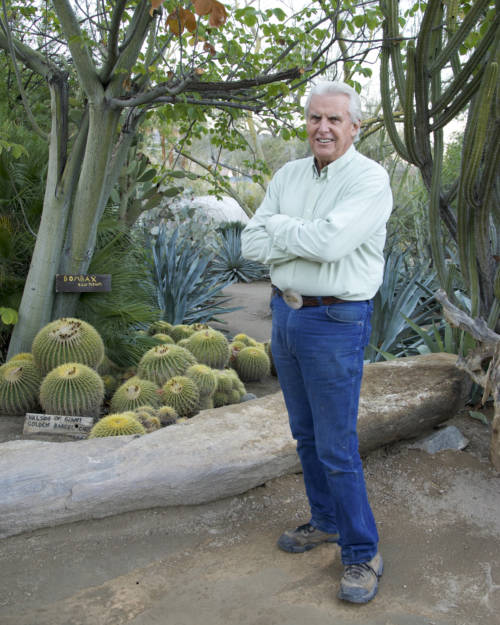

Founded in 1938, the Moorten Botanical Garden features over 3000 varieties of succulents, cacti, yucca, and other plants. (It’s also home to the world’s first Cactarium— a term coined by the Moorten family over 70 years ago.) As a result, the current owner, Clark Moorten, is never at a loss for company: the garden is visited by adventurers and garden aficionados from all over the world, and has become an Instagram phenomenon in recent months.

On a recent trip to Palm Springs, I sat down with Moorten to discuss why his father, an icon of silent film industry who was one of the original Keystone Cops, left his career in Hollywood to start a nursery in the desert. Below, we discuss Joshua Trees, Hell’s Angels, cactus smuggling, and the surprising reason why Mexico has stopped the export of all cacti.

GC: Tell us a little bit about your father, and why he started this cactus nursery.

CM: My father was born and raised in the state of Washington, in the Tacoma-Puyallup area. His mother passed away when he was 13, and his father died when he was 15, so he lived with an aunt and some friends. They all said he was such a character, he ought to go be in the movies. So in the early 20s, he hitchhiked to California and got into the movies as one of the Keystone Cops. He was around Hollywood doing character parts, but he didn’t have a great speaking voice and the talking movies were coming in. He managed to keep working, and sometimes he’d do some technical work– he worked on a Howard Hughes film, Hell’s Angels.

“After a while, he decided cactus paid better than gold did, and that’s how he got into the cactus business.”

But then he was diagnosed with pretty severe tuberculosis. He was told he was probably going to die within three to five months, and he needed to go to a sanitarium. Well, he didn’t want to go to a sanitarium; he wanted to go to the desert [and mine gold]. Around this time, he noticed the nurserymen from Los Angeles were always coming out to the desert looking for desert plants. So he said, “OK, I’ll just start collecting this and make a nursery.” After a while, he decided cactus paid better than gold did, and that’s how he got into the cactus business.

In 1938, he came to Palm Springs because he needed more access– he used to wholesale plants and he made these unique, self-made, dish gardens that he would wholesale to the nurserymen. That’s how got started in the nursery and eventually the landscaping business. My mother moved west from Ohio in the 30’s and attended UCLA for botany. She was working for a major nurseryman in Los Angeles, who my dad dealt with, and this big nurseryman introduced my parents. They got married in 1940 and formed a partnership, and eventually in the mid-50s we acquired this farm. My dad had a business for years selling dried foliage for window display. We’d literally pack 500 tumbleweeds and ship ’em to the East Coast.

GC: What was this property before?

CM: The house was here, a few palm trees, three native trees. The home was built in 1929 by a well-known photographer by the name of Stephen Willard. Everything there– big rocks, trees, big cactus– we put in.

GC: You’ve been at this for a while. Have you noticed the transition post-Endanger Species Act?

CM: It started back in the 70’s with the Endangered Species Act, when they started to try and save the grizzly bear. Then they wanted to save the flea that was on the grizzly bear, and then they wanted to save the mite that was on the flea on the grizzly bear. It started to get crazy. There was a woman who wrote an article about cacti and how they’re endangered and she thought one of the biggest problems was cactus nurseries– ’cause it was creating an interest, which was gonna make people go out and strip all the hill sites of cacti– which is a crazy idea. But this is back 50 years ago.

GC: I actually don’t think that’s such a crazy leap.

CM: Nobody wants to get on a burro and ride for three days over the hills to go find a cactus; I’d rather go to Walmart and buy a tray of ’em!

GC: How hot does it get here in the summer?

CM: Let’s put it this way: the devil won’t come here in the summertime.

GC: How do you irrigate out here in the desert?

CM: Our irrigation system here runs at night. If the stomata open on the cactus, it’s generally at night, because during the day that all closes up so they can hold their moisture, so they can absorb some moisture. But watering at night also washes them off. [Because of our recent rain,] right now everything’s really clean. I mean, today was like paradise. Absolute paradise. It sparkles. The cacti got a great bath– 2.8 inches of rain!

GC: Where do you look to find new plants?

CM: Somebody says, “Have you heard about this plant or this new euphorbia?” and we try to get some tissue culture to propagate it. Field collection of plants and wild clippings of cacti is really limited now because of conservation orders, and the international biodiversity agreement. If you discover a new plant somewhere, that becomes the property of the government. That created some problems when it was put into effect.

In Mexico, they’ve stopped the export of all cacti. You have to team up with two government officials and two people from the University of Mexico Botany Department [in order to collect]. Let’s say they go on an expedition and find some plant material– maybe very rare or very new– then they will have to leave it with the government. Then the government will finally give the OK and take it to the US Embassy and ship it up here. Mexico got really, really strict about that, for a number of reasons.

“Plants are like people. They live and they die. And the older generation is dying off. Kinda like the younger generation is trying to do to us now. They come up with all this technology that intimidates us to death.”

GC: We’re all big cacti and succulent fans. We love yucca. Today we were at Joshua Tree…

CM: Joshua trees are really an awesome plant.

GC: Is it true that the Joshua tree is endangered? Or are people just worried because of the California drought?

CM: Joshua trees, first of all, grow above 3,000 feet– they like a high, dry, cold climate. And yeah, there’s been a massive die-off of the big ones, but I’ve noticed a lot of young ones growing. They’re not a very fast-growing plant, but some of those big ones are, for whatever reason, not getting enough water. But they’ve been a protected species for the past 40 years. Years ago you could move Joshua trees if they were in a development, but then they put a restriction on it– if you want to build a house and there’s a Joshua tree in the center of it, you have to go through hoops.

Plants are like people. They live and they die. And the older generation is dying off. Kinda like the younger generation is trying to do to us now; they come up with all this technology that intimidates us to death.

That’s how this place came about. Moorten Botanical Garden has always been open to the public. To me it’s a pleasure to have this. I think it’s a pretty amazing collection, and it’s nice that we can share it with the public– and that others appreciate it, too.