Inside Virginia Woolf’s Country Garden

Monk’s House in the small Sussex village of Rodmell was Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s country retreat from 1919, until Leonard died in 1969. Virginia Woolf wrote most of her major novels at Monk’s House, and drew inspiration and comfort from the lush plantings and red brick pathways weaving through various “garden rooms.”

A terrace with antique millstones, a fishpond garden, an Italian garden, a walled garden, a vegetable garden, and a blazing flower walk were all created by the Woolfs over the years, in what would become one of the most beautiful estates in the English countryside. Starting from a very small, overgrown three quarters of an acre behind a little house originally built in the 17th century, they produced the perfect cottage garden and writer’s paradise that travelers can visit today.

Many crumbling walls, outbuildings, and an old tool shed that Virginia initially used as a writing room dotted the property when they first arrived. An orchard on the far side of the site was bordered by a 12th-century church whose steeple poked up over the trees. Leonard describes the landscape as having all the things he liked:

“a patchwork quilt of trees, shrubs, flowers, vegetables, fruit, roses, and crocus tending to merge into cabbages and currant bushes.”

As for the ramshackle house, Virginia’s sister, the painter Vanessa Bell, who lived nearby at Charleston House, helped decorate the furniture and artwork in the house, along with her companion, the artist Duncan Grant. Virginia painted the sitting room her favorite bright green color. By 1920’s standards, the living conditions– no electricity, no running water, bathroom, or lavatory– were definitely primitive.

Despite the basic conditions, the Woolf’s entertained a large circle of now famous literary and artistic friends who visited Monk’s House, including the authors T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, Lytton Strachey, and Vita Sackville-West; the economist, John Maynard Keynes; and the artist and critic Roger Fry.

A Bright, Painterly Garden

Described as organic and delightfully informal, the garden at Monk’s House was a joint project for Leonard and Virginia. Leonard, who was a political activist as well as the editor and publisher of London-based Hogarth Press, actually became an expert horticulturalist and beekeeper, and was always planting bulbs, pruning trees, harvesting honey, and vegetables, and managing a full-time gardener.

Virginia, on the other hand, conceived of the garden as her inspiration and part of her writing life. She wasn’t that interested in botany, but she liked planting a favorite tree or flower, and often helped with weeding, picking apples, dead-heading flowers, making honey, or just holding a ladder for Leonard.

The Woolf’s entertained a large circle of now famous literary and artistic friends who visited Monk’s House, including the authors T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster, Lytton Strachey, and Vita Sackville-West; the economist, John Maynard Keynes; and the artist and critic Roger Fry.

Eventually, Virginia had a proper writing lodge built in a corner of the orchard, which was filled with apple, pear, cherry, and plum trees; it had been an established orchard for about two hundred years before they arrived. Virginia bottled the fruit and she and Leonard often took baskets of apples and pears to friends and to local markets.

A separate fig tree garden– also on an ancient plot– was surrounded by old flint walls and brick paving. The Woolf’s used these walls as a starting point for the basic design and layout of the central portions of the garden– a series of rooms, divided by distinctive brick paths and flint walls. During her frequent illnesses and bouts with depression, walking through the tranquil garden paths was a great comfort and helped to soothe her mind.

To get to the writing lodge, each day she would go past the fig tree garden and fishpond garden, or down the flower walk filled on each side with mixed, giant, richly-colored blooms. She described it as:

“…a perfect variegated chintz… asters, plumasters, zinnias, geums, nasturtiums… all bright, cut from colored papers, stiff upstanding as flowers should be.”

The Bedroom Garden

Virginia’s bedroom at Monk’s House became a sitting room with “a fine view of the downs and marshes and an oblique view of Leonard’s fishpond…” In the cool, grey fall days they would sit by the fireplace and gaze outside where Virginia would see “…vast white lilies, and such a blaze of dahlias that even today one feels lit up.”

Eventually, Virginia had a proper writing lodge built in a corner of the orchard, which was filled with apple, pear, cherry, and plum trees; it had been an established orchard for about two hundred years before they arrived.

When it was too cold to write at her lodge, Virginia worked in the sitting room. The view also encompassed two large, intertwined elm trees, which they dubbed Leonard and Virginia. In 1941 after Virginia took her own life by drowning, Leonard buried her ashes under one of the elm trees in the garden marked by an engraved stone plaque. A bust of Virginia by the Bloomsbury Group artist Stephen Tomlin now sits near the plaque.

After Virginia

Leonard spent more time working and living in London after Virginia’s death, but a new friendship with another gardening enthusiast, Trekkie Parsons, gave him reasons to expand the gardens at Monk’s House with her help. Both loved exotic plants and filled a cactus house on the grounds. In the 1950’s, Leonard built a conservatory that was attached to the green sitting room. He used the space for seedlings and dahlia cuttings, but also for brightly-colored South African species.

Leonard didn’t want the house and garden to become a literary shrine although he did allow the garden to be open for the National Garden Scheme during the last decade of his life. He bequeathed some of the estate to Trekkie Parsons, who then turned over the house and the Woolf’s papers to the University of Sussex. The university rented out the house to visiting academic staff who didn’t necessarily take care of the garden, so by the late 1970’s, it was a wreck. In response, Vita Sackville-West’s younger son, Nigel Nicolson, who was editing Virginia’s letters at the time, persuaded the National Trust to take over preservation of the entire property.

A tenant of the National Trust living at Monk’s House, Caroline Zoob, who authored a wonderful book about the garden, writes about how she and her husband actually lived and worked at Monk’s House for more than a decade beginning in 2000. They planted and re-planted the gardens, looked after all the buildings, and opened the house twice a week to the paying public. Their deep understanding of the place and what it feels like to physically be there makes her book truly valuable.

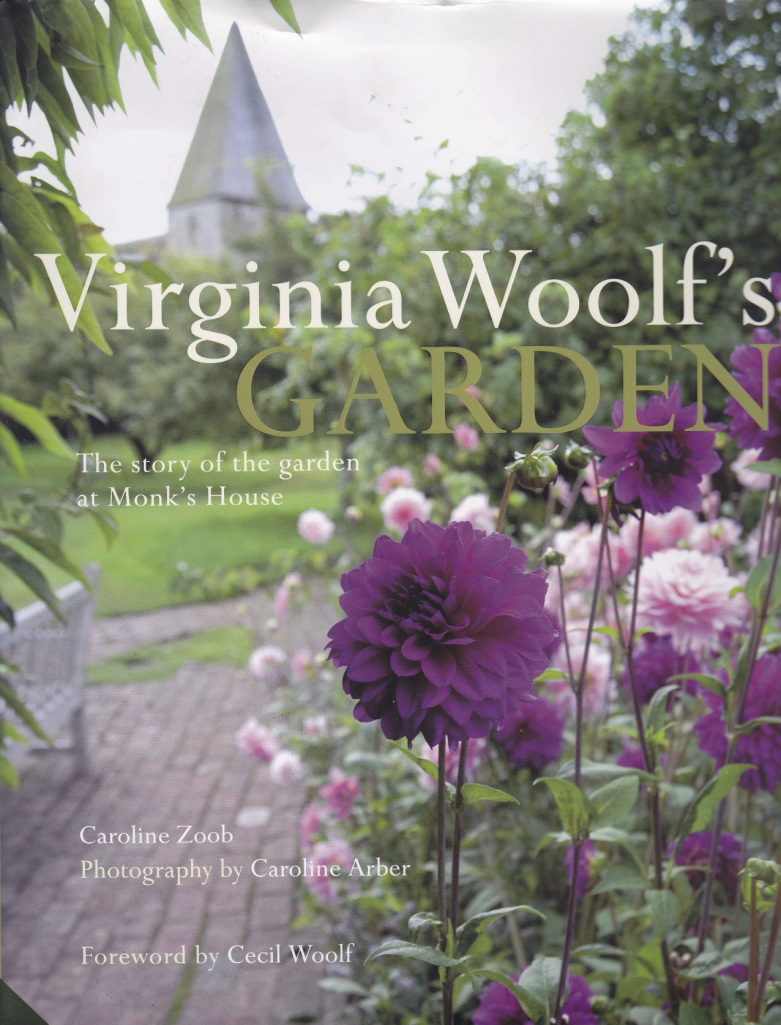

The book contains many gorgeous, contemporary full-color photographs of the gardens taken by Zoob’s friend and photographer Caroline Arber, which capture its brilliant flowers, sculptures, brick paths, charming interiors, and architectural details– with many images taken very early in the morning, before the public is allowed to visit. ([easyazon_link identifier=”1909342130″ locale=”US” tag=”gardcoll03-20″]Virginia Woolf’s Garden: The Story of the Garden at Monk’s House[/easyazon_link] is published by Jacqui Small, LLP.)

Day-tripping in Sussex

Monk’s House is located in the area of East Sussex known as South Downs National Park, which features fabulous trails and scenic views. A short distance from Monk’s House is Charleston House, the country home of Woolf’s sister Vanessa Bell, her husband Clive Bell, and her artistic companion Duncan Grant. After World War I, Charleston became a meeting place for many artists, writers, and thinkers known as the Bloomsbury Group.

Virginia often walked over the Sussex Downs to her sister’s house for visits with her niece and nephews. The house is decorated with many of Bell’s paintings, ceramics, and textiles. A lovely walled garden was designed by Roger Fry in 1919.

A few miles away is the small Berwick Church best-known as the place where Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell, and Quentin Bell, her son, painted striking murals that cover the nave walls, chancel arch, screen, and pulpit.

Also nearby is the former home of beloved author and poet Rudyard Kipling, called Bateman’s, where his family lived from 1902 to 1939. Covering 330 stunning acres, there are ancient woodlands and wonderful walking trails. Formal and wild gardens surround Kipling’s 17th century, Jacobean-style stone house, in which his book-lined study and art collection are still on view– just as he left them, for all to enjoy.

Love learning about famous authors’ gardens? Read our story on Agatha Christie’s garden in Devon, or check out our interview with Outlander author Diana Gabaldon.